Floating islands were a novelty ten years ago, but now they’re established, well-researched systems that have proved their value in fixing damaged ponds and lakes. It’s all about restoring food webs, says Bruce Kania — and learning to grow fish instead of mats of algae.

I live beside a lake on a property that also includes the headquarters for my business, Floating Island International (Shepherd, MT). The lake serves as our laboratory, and my near-constant proximity to it means that I’ve gotten to watch how the water has changed through the years.

It’s been an upward spiral:

It’s been an upward spiral:

The water keeps getting clearer, cleaner and healthier, and there’s almost unbelievable fish production.

Nature truly is our ally in this improvement – no chemicals involved!

Our observation of the water’s condition takes many forms here. It includes snorkeling with fish fry and being surrounded by hundreds of healthy, shockingly colorful fish. It includes tracking the emergence of a native freshwater sponge, a filter-feeding animal that has colonized the underside and sidewalls of research islands and quietly contributes to the increasing water clarity. And it includes cultivation of wildflowers such as Indian paintbrush, which explodes in umber orange on our islands during late summer. We’re inspired daily.

For all that, the field of water management feels a bit like the Wild West these days, with all sorts of gunslingers enforcing their own “rules” – and plenty of patent-medicine vendors peddling snake-oil panaceas. By contrast, we see ourselves, in our little corner of Montana, as the reliable marshals of a well-ordered town.

We operate with the belief that the rugged frontier territory we know as water has an incredible future – and see what we’re calling transition water as the game changer.

Our observation of the water’s condition takes many forms here. It includes snorkeling with fish fry and being surrounded by hundreds of healthy, shockingly colorful fish. It includes tracking the emergence of a native freshwater sponge, a filter-feeding animal that has colonized the underside and sidewalls of research islands and quietly contributes to the increasing water clarity. And it includes cultivation of wildflowers such as Indian paintbrush, which explodes in umber orange on our islands during late summer. We’re inspired daily.

For all that, the field of water management feels a bit like the Wild West these days, with all sorts of gunslingers enforcing their own “rules” – and plenty of patent-medicine vendors peddling snake-oil panaceas. By contrast, we see ourselves, in our little corner of Montana, as the reliable marshals of a well-ordered town.

We operate with the belief that the rugged frontier territory we know as water has an incredible future – and see what we’re calling transition water as the game changer.

BETTER AND BETTER

When we first wrote about BioHaven floating islands in the April 2005 edition of WaterShapes, ours was a fringe product seeking a market. Since then, the challenges associated with being new have faded and our scientific base has grown exponentially. Indeed, our approach to biomimicry is now being studied around the world, and a large pool of researchers is now helping to define system dynamics.

For some time now, documented benefits have included reduction of pollutants related to nutrient loads; fishery enhancement; shading and cooling of waterways; wave mitigation; and shorebird and waterfowl habitat expansion. Research has also demonstrated long-term reduction in the rate of eutrophication of waterways: As nutrients cycle into healthy, biodiverse waterway food webs, a greater fraction of those nutrients cycle out. Ultimately, this results in less accretion of system-starving organics on the bottoms of lakes or reservoirs.

For some time now, documented benefits have included reduction of pollutants related to nutrient loads; fishery enhancement; shading and cooling of waterways; wave mitigation; and shorebird and waterfowl habitat expansion. Research has also demonstrated long-term reduction in the rate of eutrophication of waterways: As nutrients cycle into healthy, biodiverse waterway food webs, a greater fraction of those nutrients cycle out. Ultimately, this results in less accretion of system-starving organics on the bottoms of lakes or reservoirs.

Often, the ponds and lakes we’re asked to address looks like this one did – a green mess carpeted with algae (left). By introducing floating islands and re-establishing an appropriate food web in which more nutrients are removed than are introduced, we set the water on an upward spiral to sustainable clarity and health.

We now describe the liquid contents of ponds and lakes that improve from green, murky and malodorous as transition water – that is, water that is in the process of becoming clear, clean and healthy.

The first study of transition water took place at our lake in Montana and revolved around a connection we saw between what we were doing and nature’s wetland effect. We’ve learned through years of observation that when surface area and circulation are tuned into a certain relationship, water gets better and better. And when we recently combined circulation systems with our BioHavens, we observed that the floating islands cycled at least four-and-a-half-times more nutrients into appropriate biota than would otherwise have been the case.

In essence, we’ve learned to grow fish instead of algae.

As a result, we’ve expanded the list of benefits cited above to include clean power generation and its associated revenue (discussed below); expanded reduction of nutrient pollution; expanded sustenance of forage fish, which, in turn, expands production of game fish; and expanded shading and cooling of waterways. Finally, and perhaps most significant in the transitioning of the water, there’s a strategic reduction of factors contributing to algae blooms.

So now we work deliberately with transition water, removing nutrients at a greater rate than they are introduced. By analogy, that’s the essence of the wetland effect: just the right relationship of surface area and circulation. Gravity, wind and waves will get this done in nature; with floating islands, we deploy air-lift pumps within the matrix and plants’ roots in transforming murky to healthy water. Where we find algae, cyanobacteria and mosquitoes, we leave behind clear water and healthy fish.

How does this happen? First, we prevent nutrient build-up, which is basic, primary watershed management. Second, we restore the food web, having learned that you don’t fix the water in hopes of resurrecting the food web but instead resurrect the food web in order to fix the water. Third, we harvest and consume the fish – particularly the young ones in which toxins haven’t accumulated.

The first study of transition water took place at our lake in Montana and revolved around a connection we saw between what we were doing and nature’s wetland effect. We’ve learned through years of observation that when surface area and circulation are tuned into a certain relationship, water gets better and better. And when we recently combined circulation systems with our BioHavens, we observed that the floating islands cycled at least four-and-a-half-times more nutrients into appropriate biota than would otherwise have been the case.

In essence, we’ve learned to grow fish instead of algae.

As a result, we’ve expanded the list of benefits cited above to include clean power generation and its associated revenue (discussed below); expanded reduction of nutrient pollution; expanded sustenance of forage fish, which, in turn, expands production of game fish; and expanded shading and cooling of waterways. Finally, and perhaps most significant in the transitioning of the water, there’s a strategic reduction of factors contributing to algae blooms.

So now we work deliberately with transition water, removing nutrients at a greater rate than they are introduced. By analogy, that’s the essence of the wetland effect: just the right relationship of surface area and circulation. Gravity, wind and waves will get this done in nature; with floating islands, we deploy air-lift pumps within the matrix and plants’ roots in transforming murky to healthy water. Where we find algae, cyanobacteria and mosquitoes, we leave behind clear water and healthy fish.

How does this happen? First, we prevent nutrient build-up, which is basic, primary watershed management. Second, we restore the food web, having learned that you don’t fix the water in hopes of resurrecting the food web but instead resurrect the food web in order to fix the water. Third, we harvest and consume the fish – particularly the young ones in which toxins haven’t accumulated.

The population of our research base, Fish Fry Lake, includes species of multiple sizes and varieties, each with a role in the food web. The Fathead minnows (left) are so successful that we frequently harvest them for transfer to other bodies of water where their skills in feasting on mosquito larvae make them much in demand. These minnows also support a variety of predators (right), but the island habitats give the minnows places to hide, reproduce and maintain a bountiful presence.

THE SOLAR CONNECTION

So take a lake that is, today, a green pancake of filamentous algae or, worse, a lake that is a malodorous mosquito factory: Introduce a floating, streambed-equipped island sized for that lake’s specific surface area, activate the circulating mechanism and, soon, it’ll be time to outfit owners and their visitors with fishing poles and creels. In due course, the water will move from murky to clear, the animals will thrive and it’s likely that there will be enough fish that it might be necessary to call in game regulators to make sure applicable standards for harvestable waters are being met.

I made a point just above that can’t slip by: We are indeed adding circulation systems to our floating islands, because we’ve found it’s the swiftest way to achieve the transition from murkiness to sustainable clarity. But all of us who’ve worked with substantial water projects know about skyrocketing costs. Just the measurement component of a large project, such as the cleanup of Chesapeake Bay, approaches the billion-dollar mark all on its own.

Only solutions that pencil out with actual, significant return on investment have any real prospect of going forward, and that’s why the current generation of streambed - including floating islands are different from what we produced in the past. While they still concentrate nature’s wetland effect, cycle nutrients into fish, mitigate wave action, beautify waterways and create new and strategic wildlife habitat, they are now also used as incredibly stable platforms upon which roads, buildings or pretty much any human activity can happen – and this includes supporting megawatt-scale solar energy arrays we use to power our circulation systems and generate substantive revenue at the same time.

I made a point just above that can’t slip by: We are indeed adding circulation systems to our floating islands, because we’ve found it’s the swiftest way to achieve the transition from murkiness to sustainable clarity. But all of us who’ve worked with substantial water projects know about skyrocketing costs. Just the measurement component of a large project, such as the cleanup of Chesapeake Bay, approaches the billion-dollar mark all on its own.

Only solutions that pencil out with actual, significant return on investment have any real prospect of going forward, and that’s why the current generation of streambed - including floating islands are different from what we produced in the past. While they still concentrate nature’s wetland effect, cycle nutrients into fish, mitigate wave action, beautify waterways and create new and strategic wildlife habitat, they are now also used as incredibly stable platforms upon which roads, buildings or pretty much any human activity can happen – and this includes supporting megawatt-scale solar energy arrays we use to power our circulation systems and generate substantive revenue at the same time.

Our lake supports the most productive fishery in the State of Montana, but as can be seen on the underside of this island, it also supports a native species of freshwater sponge that found its way into the lake without our intervention, perhaps via the root system of an aquatic plant. They are filter feeders and remove phosphorus and other nutrients from the water, contributing significantly to the health of Fish Fry Lake.

That last point is the economic key: With large solar arrays, floating islands effectively pay for themselves as they go – and more. Indeed, we see the linking of solar-power generation to water cleanup as the next step on the path.

For all that, our goal is (and always has been) to bring eutrophic and hyper-eutrophic water back to a more pristine state. Once the water comes back, we can then focus on reintroducing prized coldwater species such as trout – although it’s probably best to focus at first on native warm and coolwater species until the water is consistently healthy again. These species include native minnows, which are extremely strategic relative to nutrient cycling. Some, like fathead minnows, are also effective predators of mosquito larvae.

Once the forage-fish base is firmly established, panfish and other sport fish can follow – and floating islands will sustain their spawning and provide them with secure habitats. That’s important, because without physical security, the forage fish species will likely be preyed upon by larger fish and will vanish, thereby disrupting the food web and limiting that ecosystem.

Today, our Fish Fry Lake is incredibly productive. It’s why 15 kids – some as young as seven years old – recently caught 879 panfish, northern yellow perch, bluegill, green and red-ear sunfish and largemouth bass in five hours. It works because we meticulously manage the complete food web, from biofilm and diatom-based periphyton to sport fish and those surprising freshwater sponges.

For all that, our goal is (and always has been) to bring eutrophic and hyper-eutrophic water back to a more pristine state. Once the water comes back, we can then focus on reintroducing prized coldwater species such as trout – although it’s probably best to focus at first on native warm and coolwater species until the water is consistently healthy again. These species include native minnows, which are extremely strategic relative to nutrient cycling. Some, like fathead minnows, are also effective predators of mosquito larvae.

Once the forage-fish base is firmly established, panfish and other sport fish can follow – and floating islands will sustain their spawning and provide them with secure habitats. That’s important, because without physical security, the forage fish species will likely be preyed upon by larger fish and will vanish, thereby disrupting the food web and limiting that ecosystem.

Today, our Fish Fry Lake is incredibly productive. It’s why 15 kids – some as young as seven years old – recently caught 879 panfish, northern yellow perch, bluegill, green and red-ear sunfish and largemouth bass in five hours. It works because we meticulously manage the complete food web, from biofilm and diatom-based periphyton to sport fish and those surprising freshwater sponges.

TRANSITION STATES

In our research, we’ve seen that the real key to system health is cycling nutrients into diatom-based periphyton instead of to the default biota – that is, other forms of phytoplankton and cyanobacteria. In effect, the whole lake is energized by dint of combining a consideration of surface area with an appropriately sized circulation system. This energy encourages the growth of biofilm/periphyton and the penetration of sunlight that grows diatoms instead of a mono-culture of algae. Diatom-based periphyton feeds forage fish and helps nurture sport fish, too. The food web, in other words, has been restored to great effect.

|

The Lake’s Story

Fish Fry Lake started off as a seasonal pond in a swale. That swale drained a few hundred acres of irrigated ground along the Billings Bench, one of the oldest irrigation ditches in Montana. The surrounding acreage had been intensively farmed for many decades before we arrived. Most of the swale was developed to create Fish Fry Lake. But as the heavy equipment roared, we noticed that the swale had also included a dump site where we found bags partially filled with fertilizer. They’d probably gotten wet or old, and a past farmer, because fertilizer was cheap, took the easy way out when it came to disposing of it. At that time, I didn’t understand the potency of fertilizer. If I had, I may have reconsidered creating Fish Fry Lake. But we kept at it, and, all told, it took us three years to define the lake’s perimeter. We brought in many tons of cobble and gravel, various fish structures and more. As a fishing guide and an avid fisherman, I drew from my experience and the advice of many experts to design a wonderful fishing lake. Imagine my amazement when, within days of the lake being filled, it was totally covered by a carpet of algae. No open water was visible at all. We’d also dug out a smaller pond on the property – one directly filled by ditch water, so it did not experience the sort of groundwater inflow that was true of Fish Fry Lake. The water here was beautiful for a time, but late in the summer the first year after the small pond had been dug, my black dog’s coat would take on a reddish hue when he emerged from the water and he would stink. So now both waterways were experiencing some form of pollution. Floating islands have changed all that and, eleven years later, Fish Fry Lake is clear and stays that way – and it’s all because we figured out how to mimic nature and were patient enough to take our transition water from malodorous murkiness to near-crystalline clarity. And it just keeps getting better! — B.K. Vertical Divider

|

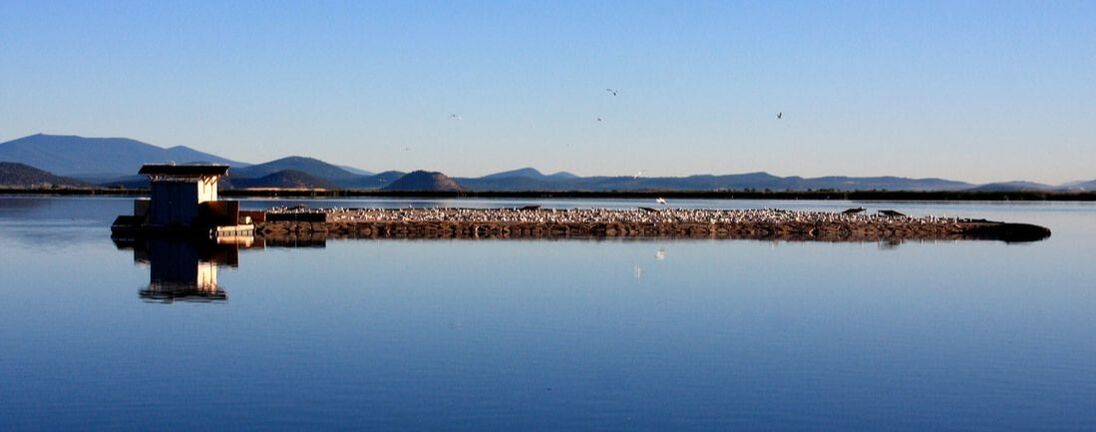

View of an acre-sized, 27-inch-thick island floating on a reservoir in Northern California. It’s covered by tons a gravel as a safe habitat for a specific species of tern (as well as a range of other birds) and floats in deep water, so even in a time of drought, it’s been inaccessible to land-based predators. In addition, it also hosts a small solar array that takes care of the island’s ongoing electrical demand.

BioHaven islands facilitate the path to transition. And now that they are capable of paying for themselves by generating solar power, questions about scalability are easier to answer.

It may still be the Wild West out there, but imagine public waterways in which floating islands multitask, benefiting life forms under the water line by cycling nutrients through the food web, introducing new plant growth on top of islands, and providing secure spawning habitats – all this while also serving as floating walkways, fishing piers, rafts for solar arrays, boat docks (and even actual marinas). What a wondrous way to transition water back to health! Floating islands have come a long way in the past ten years, and Fish Fry Lake offers a model that can be applied almost everywhere. Bruce Kania is founder of Floating Island International of Shepherd, MT, and an inventor with a successful track record in the licensing of product concepts in the prosthetic, orthotic, textile and sporting-goods industries. He originated the idea of replicating natural, self-sustaining floating islands while working at his research farm in eastern Montana. He also runs a think tank for independent contractors through his company, Fountainhead, LLC of Bozeman, MT.

|